By: Sara Flanagan, Assistant Professor of Special Education, University of Maine & Tammy Mills, Senior Lecturer of Education, University of Maine

Writing can be difficult for students from learning to form a sentence to a formal paper. The writing process demands the simultaneous coordination of multiple tasks, including spelling and reading, brainstorming and organizing ideas, sentence and paragraph formation, and applying foundational knowledge such as punctuation rules. When students encounter difficulties writing, they may not effectively communicate their message and errors in spelling and grammar can exacerbate these challenges. A teacher might not realize that “we have all but this one in the serys of the books we wonte beabul to read the seres of books and sumthing important hapins in the one thats mising” in response to a prompt on what book a library should buy and why reads, “We have all but one in the series of books. We won’t be able to read the series of books, and something important happens in the one that’s missing.” Students may rephrase a prompt without providing details or by providing off-topic information, or they may repeat the same idea several times. Students may not understand writing requirements such as having a topic sentence followed by relevant, supportive detail sentences (Graham, 2019; Mather et al., 2009).

Students who struggle with writing may receive lower grades or may not complete writing-related tasks successfully. Like the student writing about a library book, the lack of sentence structure and other errors prevents their teacher from understanding their ideas about the book or fully assessing their writing. To support students’ writing, students need explicit instruction with strategies like graphic organizers and technology.

WRITING STRATEGIES

Explicit instruction (EI), or the Graduate Release of Responsibility model, is an effective instructional model for writing and instruction broadly (see Table 2 online for an example). This provides a systematic, structured approach to teach any topic by providing a model then practicing together, in pairs or groups, and independently. Students are given feedback throughout to know if they responded correctly (or, incorrectly) and why. EI is particularly effective when introducing a new topic or one with multiple components, or when students may not understand the needed prerequisite skills (Archer & Hughes, 2010).

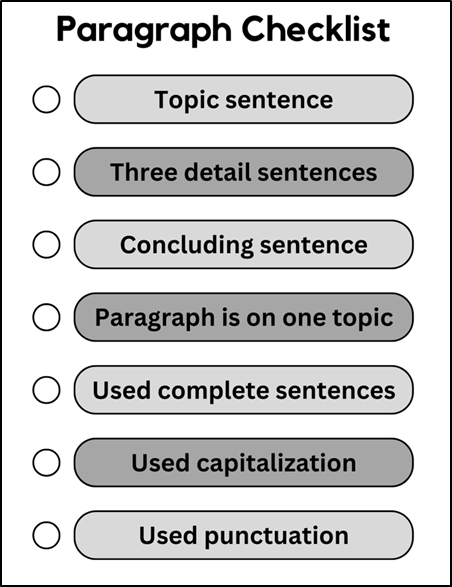

For writing, EI instructional elements like providing the needed background information, models of a writing task, graphic organizers or other scaffolds, and feedback are effective practices (see Table 2 online for resources). Reviewing background information such as writing-related vocabulary prior to instruction ensures that all students have the prerequisite knowledge. Models, or exemplars, allow students to see the finished product and identify models of different quality and determine why (Berger et al., 2013). For example, if instruction is on writing a complete sentence, a teacher might demonstrate this several times to explain what is a “good” sentence, and then show sentences with missing components to discuss how to correct these. Graphic organizers and concept mapping provide a structure for the writing task, and allows students to brainstorm and organize content before writing. These are useful for students because a similar structure can be used across grade levels and writing tasks from writing a sentence to a paragraph to a science lab report.

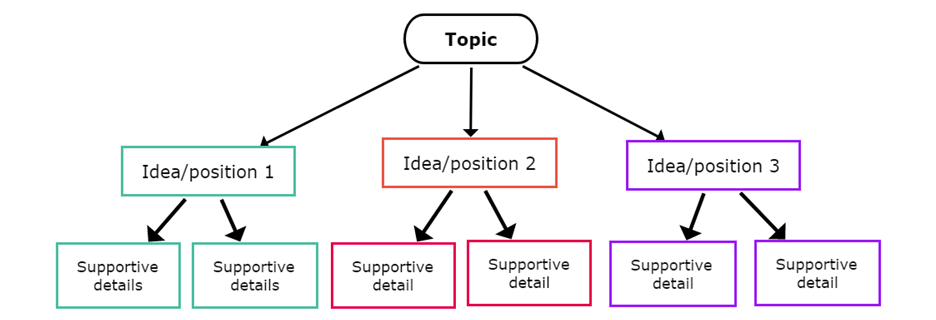

Technology supports writing with many tools embedded in students’ computers and devices. Typing, word prediction, and spelling and grammar check reduce reliance on physical handwriting and spelling, allowing students to focus on developing their content. Students can dictate (i.e., speak) instead of type, and then listen to their content using a screen reader for editing. Technology potentially increases motivation by creating more authentic and engaging writing tasks, such as creating a digital storybook instead of writing an essay. Authentic writing tasks provide students opportunities to express themselves to varied audiences for multiple purposes. If a writing task is relevant, students are motivated to engage with feedback, revise, and use writing strategies they find helpful for them. Writing with a clear purpose and audience in mind encourages students to craft compelling pieces, from letters to essays to social media posts. Last, an essential step of any writing instruction is feedback through written comments, conferencing, rubrics, or other strategies like peer-editing. It can be as straightforward as a checklist of required writing components. Any type of feedback allows students to know what they are doing correctly and why, areas of improvement and why, set writing-related goals, and for teachers to monitor students’ progress. While writing can be challenging for students, strategies like the ones described can support all students’ writing.

Table 2. Writing instructional resources

| Useful Links and Information | |

| General writing resources | Self-Regulated Strategy Development Model (comprehensive strategy across grade levels and writing tasks) at https://thinksrsd.com/ or text Best practices in writing instruction text Writing resources from Reading Rockets (elementary focused) Reports: Teaching elementary students to be effective writers Teaching secondary students to be write effectively |

| Graphic organizers & concept mapping | Information and examples from Reading Rockets on using prewriting and concept mapping in the classroom Other graphic organizers: OCALI (autism organization) Understood.org for a variety of writing tasks Student interactives (technology-based) from ReadWriteThink.org Templates for reading and writing from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt |

| Technology | Technology-based concept mapping allows students to quickly create and edit concept maps, examples: Younger students: Bubbl.us and Popplet Upper elementary and above: Mindmeister and Mindomo Authentic, shareable products like infographics (ex. Canva) and digital books (ex. Pixton, Storybird) to increase motivation and engagement Embedded tools within a computer or device like spelling and grammar check, or dictation (example) to reduce students’ barriers to writing like spelling and handwriting Software provides a comprehensive tool like Read&Write for reading and writing with word prediction, text-to-speech, dictionaries, and other features Grammarly or other artificial intelligence (AI)-based tools for feedback on grammar rules, structure, and spelling Use AI to create writing exemplars to use during instruction (example) |

| Feedback | Assessment examples and more information Specific feedback on both strengths and areas of growth; target areas aligned to the instructional goals to save time and focus the feedback Use Google Docs or other platform to create a shared document for the teacher (or, a peer) to provide feedback and the student to respond Create a checklist of the required components of a writing task to give students quick feedback, self-check, or peer review; for example, this editing checklist Using peer reviews (elementary and secondary examples) |

Figure 1. Example concept map and feedback checklist

Sample concept mapping template (from https://www.mindomo.com/) for a writing task with three main ideas and two supportive details for each. This could be used to write a single paragraph or longer passage with a paragraph for each idea.

Sample checklist for a paragraph with a topic sentence, three detail sentences, and a concluding sentence that a student could use to check their own writing, for peer editing, or for a teacher to provide quick feedback.