What Needs to Be Done to Tackle the Educator Shortage

The root cause of educator dissatisfaction and frustration is a lack of staff, support and respect, and not a perceived inability to manage stress. To prevent an exodus from the profession, MEA believes district and elected leaders need to act now.

Key Takeaways

- According to a recent MEA member survey, a staggering

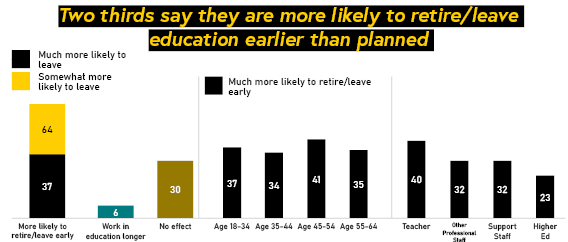

64 percent of educators say they are thinking about leaving the profession earlier than planned. - While fallout from the pandemic could be the breaking point, the educator shortage and dissatisfaction with working conditions are root causes of the problem.

- To address the crisis, MEA is working on solutions to help educators now, and the profession in the future.

Jeans Friday and extra coffee and donuts are not the answer to decrease stress among educators, according to those working in schools. Instead, acknowledging what’s causing the stress is the answer, and educators across the nation, and right here in Maine have no problem sharing the real issues facing the profession.

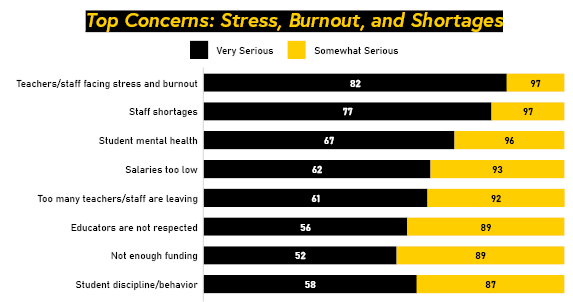

While a recent MEA member survey revealed higher pay is needed, and is a top priority, other issues are also now likely to cause educators to leave the profession. A lack of support, staff shortages, student mental health, and being part of a profession that is routinely undervalued have more citing a desire to exit education sooner than expected.

Seven in ten MEA members say they’re dissatisfied with their working conditions, with 97% saying stress is a concern. Perhaps even worse, a staggering 64% of members surveyed say they’re more likely to leave the profession or retire early. That’s nine percent higher than a recent NEA national survey asking the same question. Making the numbers perhaps more concerning, Maine already has an older teaching population who are set to retire due to age within the next five years.

Erin Castillo, now in her ninth year of teaching, is fed up with the undue pressure that she and her colleagues are facing. What she isn’t suffering from, however, is “burnout”— an overused phrase that she believes amounts to a form of gaslighting.

“What many of us are feeling is beyond burnout,” said Castillo. “This isn’t on the individual. We’re being set up to fail at this point. When the system does not allow for success, we are being demoralized.”

Educators can and have certainly burned out, says Doris Santoro, professor of education at Bowdoin College but demoralization may be a more accurate term to understand the roots of educator dissatisfaction and exhaustion.

“The burnout narrative comes down to, ‘Sorry, you blew it! You couldn’t hack it, you didn’t preserve yourself,’” she explains. “With burnout, there’s nothing left, no possibility for regeneration. If you are demoralized, however, you are not done.”

Before the recent staff shortages, educators were already dealing with less time for planning and collaboration, high stakes testing, and the silencing of educator voices. These and other trends have eroded what Santoro calls the “moral rewards” of teaching.

And while it’s critical to address the current staffing crisis, that success could be short-lived without systemic changes. “Schools should be asking educators: What are the systems that we can put in place so you can do the work that you think matters most? It comes down to support, resources, and autonomy,” Santoro adds.

Addressing Staff Shortages, Stress & Pay

Attracting educators to the profession is crucial to help reduce the stressors associated with teaching and learning. MEA is working with lawmakers in Augusta to create solutions that maintain the integrity of teacher certification while also removing bureaucratic barriers that keep qualified educators out of the classroom.

“There are so many open positions in our schools across the state- ed techs, teachers, bus drivers, and more. The Maine Education Association is focused on working with lawmakers who create the rules around who is not only allowed to apply for these jobs, but who is qualified. MEA believes we must maintain the integrity of our great profession, but we must also create reasonable solutions and pathways for qualified applicants to earn the opportunity to work in our schools,” said Grace Leavitt, President of the MEA.

With that thought, MEA is working with several lawmakers to push for changes to help support our schools, staff and our students. Among the top priorities: increasing the starting teacher salary to $50,000, lifting the minimum wage to help recruit more support staff, and expanding educator pipelines. “By broadening the pool to recruit people to the profession we can help fill shortages in our schools. MEA believes the creation of a Teacher Residency program, and one similar for ed techs will allow aspiring teachers throughout Maine to get paid while they continue to take classes to earn their degree and certification,” added Leavitt.

Currently, the University of Southern Maine runs a Teacher Residency program where almost 40 students are enrolled, and 70 more expected next fall. The program, which is open to education students throughout the UMaine System, and students from other colleges allows school districts to hire the education students to work as ed techs or long-term subs. In turn, the hiring schools provide mentors and pay students a regular salary.

“The new program fills a much-needed gap in our schools while allowing our aspiring educators to gain the experience needed to become full-time teachers one day. Finding a funding solution, at the state level, to expand the new residency program at USM can help keep our current education students enrolled in their pre-service teaching classes and graduate ready to work in our schools,” added Leavitt.

Back in the Classroom

When Castillo thinks back on her first days in the classroom, she remembers her enthusiasm, dedication, and eagerness to do everything that was asked of her at any hour of the day or night. She is still passionate about teaching and dedicated to her students. But she says she has learned to set boundaries and has a clearer understanding about the root causes of educator exhaustion and how to address it.

“I think about my own children. I want their teachers to be treated with respect, so they can walk into the classroom and give my children and my children’s friends a great public education,” she reflects. “What keeps me here is that, as a union member, I still have a voice, and it’s stronger inside the classroom than outside of it. I know what changes need to be made.”

*Some information in this article appeared in NEA Today

Get Involved

You can share your thoughts on these issues with those making the policy decisions that impact your life and work. Lawmakers in Augusta have a major impact on all these issues, and they need to hear from you. Now is the time to share your story. Tell lawmakers about what it’s like to work in our public schools. Tell them why pay needs to be increased. Share why you need more support, and a way to help reduce staff shortages. Click the link below to find out which lawmakers represent your area and introduce yourself. Lawmakers want to hear from our educators, and this is your chance to make that connection!