Just four short years ago, Zach Wentworth wrote his college application essay to the University of Maine about his passion for education and his dreams of returning to serve communities in rural Maine—like Calais where he grew up. Now, as he approaches the completion of his educator preparation program and readies himself to begin his career as an educator, the harsh realities of the current teaching profession in Maine have set in.

“Currently, teachers in my hometown of Calais earn about $40,000 per year—the state’s current minimum salary for teachers,” Wentworth explains. “With monthly rent for a one-bedroom apartment over $1,200, grocery prices increasing, student loan payments, and other basic living expenses, it is difficult to see how I could sustain myself on that salary.”

As a result, Wentworth has made the difficult decision to delay his teaching career, choosing instead to attend graduate school and work part-time. He says he hopes that things will change over the next two years, but his story is not unlike many other aspiring educators in Maine.

Upon graduation, he says many of his peers at University of Maine are choosing to forgo teaching for careers that offer competitive professional salaries like technology, business, and law. With fewer pre-service educators choosing to work in Maine’s schools, declining enrollment and completion numbers in education preparation programs, and many educators trending closer to retirement, the educator shortage in Maine is now at a crisis level.

According to data from Maine Public Employees Retirement System (MainePERS), the state is losing upwards of 1,400 teachers each year. With less than 500 students completing teacher preparation programs annually, Maine is grappling with a convergence of challenges that exasperate the shortage.

Kendrah Fisher, 7th grade teacher at SoDoMoCha Middle School in Dover-Foxcroft, is in her second year of teaching. “We do have amazing teachers in our schools, but also thousands of certified teachers who are choosing not to teach because they cannot afford to,” Fisher says.

“After taking only my net income and subtracting the cost of necessary expenses, I would be left with -$21.19 each month,” Fisher said. “I have had colleagues share with me that when they began teaching, they relied on food stamps to support their family. Others I know left teaching because the cost of childcare exceeded their pay.”

Losing educators comes at a significant cost. Dr. Erin Beal, an instructional coach at Lyman Moore Middle School in Portland, told members of the Education and Cultural Affairs Committee during a hearing for LD 34: An Act to Increase the Minimum Salary for Teachers, teacher retention issues due to low starting salaries cost a school district, on average, $20,000 for each turnover.1

The educator shortage extends beyond financial costs, impacting student learning and overall education quality. From pre-service educators to college faculty and staff, low pay and deteriorating working conditions lead to accelerated rates of burnout, sometimes causing educators to reluctantly leave for higher wages outside of public education.

“As an instructional coach, I know that teacher turnover events have even deeper ramifications for students,” Beal told the committee. “It is no coincidence that as turnover events are increasing, student test scores are decreasing. If we want to increase student learning outcomes, we must increase teacher retention and pay.”

The last change to the teacher minimum wage law was in 2019, when Maine increased the minimum pay for teachers from $30,000 to $40,000—a change implemented incrementally over three years. Despite this increase, Maine still ranks 37th in the nation for average starting salary based off 2023 data from the NEA—and still last in New England.

Making things worse, the average salary for classroom teachers has increased at a rate far slower than inflation. According to the Maine Economic Policy Center, when adjusted for inflation, the $40,000 minimum teacher salary in the 2022-2023 school year effectively represented a 7% reduction in real wages compared to when the bill passed in 2019.

This is a problem that Dr. Beal says impacts not only early career educators at the lower end of the salary scale but teachers at every level. “Salary increases for the rest of our careers depend on those early years,” Dr. Beal explains. “Despite having my doctorate and over ten years of teaching in Maine, I still can’t afford housing with a second bedroom. And in Maine, without a second bedroom, I cannot realize my deepest dream of becoming a foster mom.”

If lawmakers are serious about the future of Maine’s workforce and educating the next generation of Mainers, they must invest in its educators—Maine’s future depends on it.

“Under the current salary scale, I can help Maine children professionally, or I can help them personally,” Beal explained. “It is fiscally impossible, even with the highest level of education and experience, to do both. Please do not make me choose.”

1 Johnson et al (2019): Educator-Recruitment-and-Retention_Edited-f11dea93f2d2e1a3.pdf

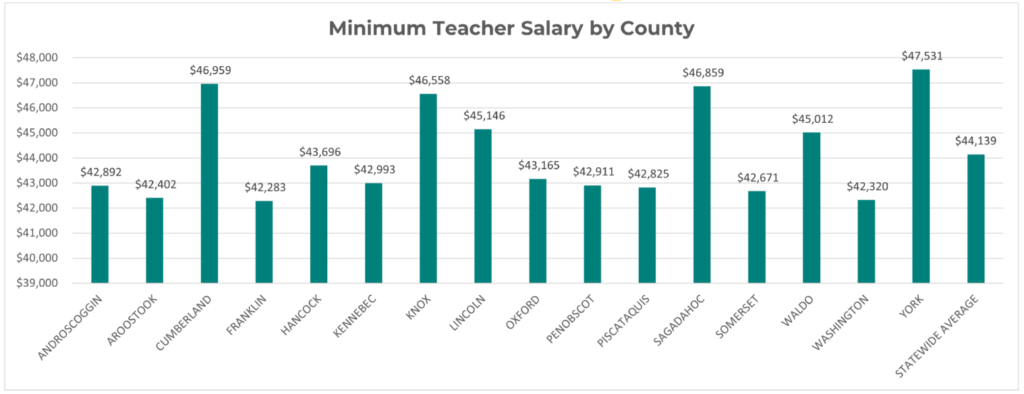

Inside Salary Data

- $39,101 – 2023 Maine Average Starting Pay

- $44,139 – 2024 Maine Average Starting Pay

- $47,531 – York County with Highest Starting Salary

- $42,283 – Franklin County with Lowest Starting Salary

53% Decline in completion of teacher prep programs since 2010

815 Teachers Quit or left the profession last year